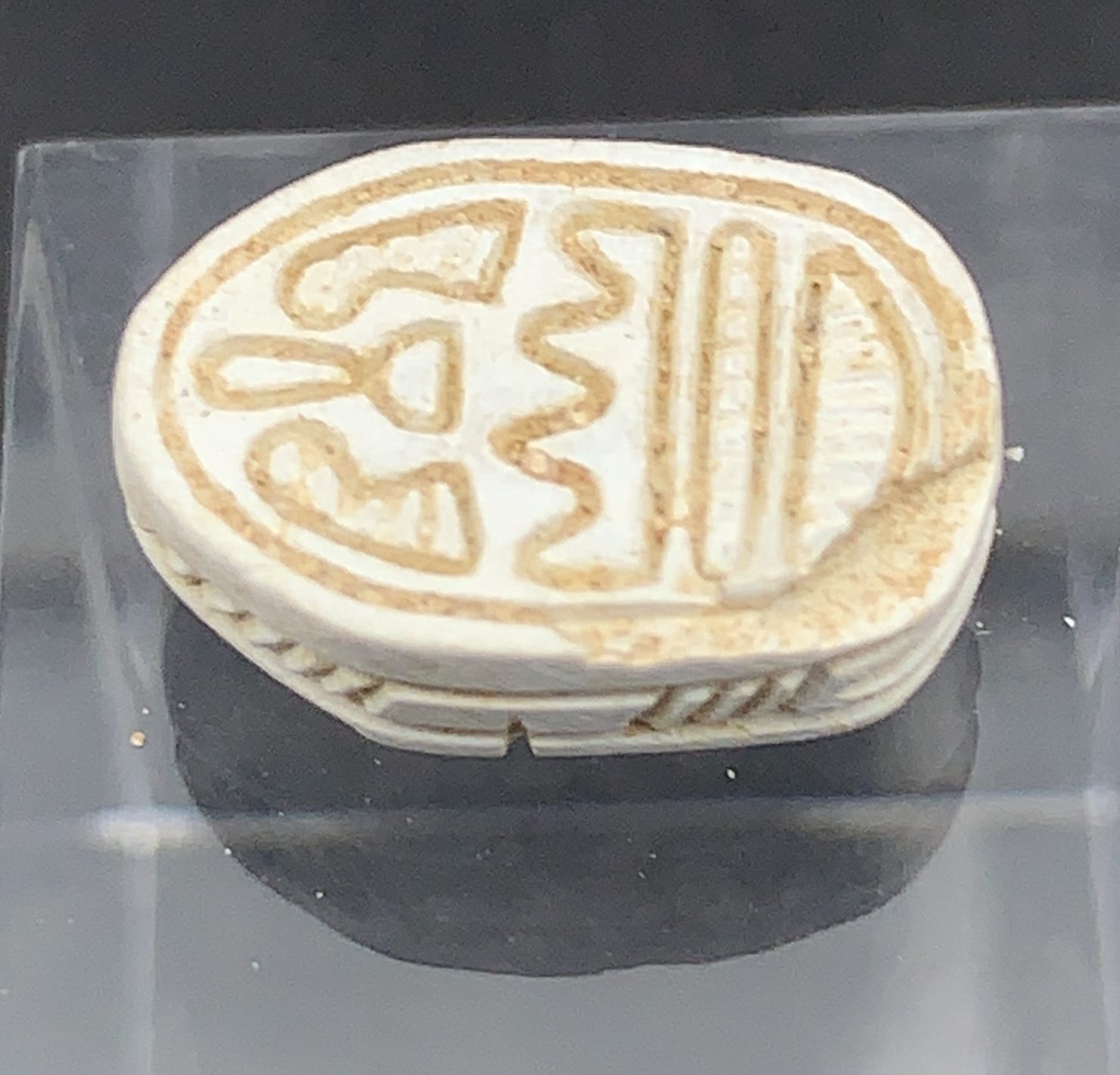

Con funerari de la tomba de Ramose

€200,00

Con funerari de la tomba de Ramose. Dinatia XVIII.

- Procedència: Egipte

- Època: 1479-1473 A.C.

- Tamany: 8 x 5 cm

- Material: Terracota

- Estat: Bona qualitat dels jeroglífics. Dues meitats enganxades

- Comprat a: Particular

- Venedor: Mohamet

- Preu: 200 $

- Certificat d’autenticitat: No

- Data: oct-00

Codi: EGY-00001

Con funerari de la tomba de Ramose. Dinatia XVIII.

- Procedència: Egipte

- Època: 1479-1473 A.C.

- Tamany: 8 x 5 cm

- Material: Terracota

- Estat: Bona qualitat dels jeroglífics. Dues meitats enganxades

- Comprat a: Particular

- Venedor: Mohamet

- Preu: 200 $

- Certificat d’autenticitat: No

- Data: oct-00

Descripció detallada

Con funerari de la tomba del Visir Ramose. Tomba TT55. Zona de Sheikh Abd el–Qurna. XVIII dinastia. Regnat d’Amenhotep III i Amenhotep IV.

Jeroglífic: Tu que adores Re a l’alba, el noble hereditari, amic únic, el primer entre els grans, governador de la ciutat, Ramose, justificat.

Més informació

FUNERARY CONES:

Artifacts, often in a conical shape made of fired clay bearing stamped funerary text on their circular face, are generally referred to as funerary cones. Though only (about) two sets of these objects have been found in situ, we believe they were inserted as a frieze, with the stamped face exposed, above the doors of Middle and New Kingdom (particularly the 18th through 26th Dynasties) private tombs. These funeral objects were produced for both men and women.

Wiedemann published the first real study of these stamped objects in 1885, which was followed by an additional systematic corpus of the objects by Daressy in 1893. However, a corpus of facsimiles compiled by Norman de Garis Davies and M. F. Laming Macadam, known as A Corpus of Inscribed Egyptian Funerary Cones, published in 1957, provides the key reference source for their study today.

While the Theban necropolis has yielded most known funerary cones, they have also been discovered in a few other locations including as far south as Nubia. The stamped text typically bears the names and titles of the deceased person, often including additional biographical data and epitaphs. Any number of cones might exist for any one person, and they provide us with a considerable amount of the information on many non-royal ancient Egyptians.

The cones may have been used for a variety of functions. Egyptologists suggest that they may have been used to identify the tomb owner (almost like a modern cemetery marker, as an ornamental memorial, as a boundary marker or even as a symbolic offering of bread or meat. Others believe that they may have been used as a symbolic tomb seal, and may been intended to provide protection. Even the stamped, conical end of the cone has been interpreted in several ways. Some believe it represents symbolically the the ends of roofing poles, a form of visitors’ card, simply a decorative element, or possibly even the shape of the sun disk.

In reality, the use of these cones is complicated by their variety. While we generally refer to these stamped objects as cones, they could be rectangular, wedge-shaped, flat or bell shaped, and at least one example took the form of a double-headed cone. Their width, length and thickness could also vary considerably, and some of the cones were even hollow. Cones are often found that were painted in various colors, mostly consisting of red, blue or white. But in ancient Egypt, these colors could indicate different materials, including bread, meat, pottery and the red glow of the sun.

In fact, some Egyptologists suggest that the investigation and handling of artifacts referred to as funerary cones has not met the same standards as other pottery items. In fact, collectors and even well known Egyptologists have sometimes mutilated funerary cones in order to preserve only the text, without regard to the objects original shape. Even Petrie admitted to this practice, stating that:

“as the inscriptions are all that is really required, the bulk of the cone was removed, either by sawing, if soft, or breaking, if hard. Thus with a very small loss, I reduced a collection of over 250 to a more manageable bulk. ”

The earliest of these cones, have been dated to the eleventh dynasty, but have no inscriptions. Some were very large, measuring some 53 centimeters (20 inches) in length, but their size decreased, particularly during the New Kingdom. They seem most common from the reign of Thutmose I, but apparently their used declined during the Ramessid period.

While funerary cones are mostly associated with the West Bank at Thebes (modern Luxor), they have also been found at Naga ed-Deir and el-Deir north of Esna. Though the tombs they reference have not been discovered, they was probably located in those general areas.

Also, Middle Kingdom tombs at Rizeiqat, Armant, Naqada and Abydos have yielded uninscribed cones. However, beyond these few other cones, none have been found outside of the Theban necropolis.

Most of the cones come from painted, as opposed to sculpted tombs, and conform to the Theban funerary traditions. They may have been thought to be particularly suited to rock cut tombs. They have been discovered in various sections of the Theban West Bank, and are particularly notable in the tombs at Sheik Abd-el-Qurna, dating to the eighteenth dynasty, but are notably mostly absent at Deir el-Medina, where only one example has been discovered.

One of the facets of Egyptology that funerary cones indicate is that their are many more tombs to be discovered. Some of these tombs may be lost to us forever, but currently there are more than four hundred funerary cones that are not immediately assignable to a known tomb at Thebes.

RAMOSE TOBM (TT55)

Ramose was a Governor of Thebes and Vizier during the 18th Dynasty during the reigns of Amenophis III and Amenophis IV (Akhenaton, the heretic king). There are no children seen in any of the decorations of his tomb, so we assume he and his wife, Meryet-ptah were childless. We believe his father to have been Neby, who served in northern Egyp as a superintendent of Amen’s cattle and in the delta as the temple’s superintendent of the granary. His mother was Apuya.

Ramose’s tomb in the general region of the Tombs of the Nobles, specifically at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna on the West Bank at Luxor (ancient Thebes) is well done for a private tomb, particularly considering that many of the scenes are in relief. It is also fairly large for a private tomb. The tomb was first made known to the modern world by Villiers Stewart in 1879, who returned to do more work on the tomb in 1882. Gaston Maspero continued the work of Stewart, but it was Robert Mond, working for the Metropolitan Museum of Art who restored the tomb to its present condition in 1924.

The tomb was unfinished, probably because Romose started construction on a new one at Amarna when his pharaoh moved the capital to his new city. But because of these changing times, the tomb is significant in that the artwork begins to show the transition to the new artistic style of Amarna. Also, because it was abandoned, it gives Egyptologists evidence on the different stages of carving and decorating a tomb.

This tomb, numbered TT 55, is traditional in its T-shaped design. One enters by a split stairway with a center ramp that leads into the courtyard, both of which are outside the tomb proper. From there a short stairway leads to a large hypostyle hall with 32 columns. This was the only room in the tomb that was decorated, though the rooms behind it were prepared for decorations. Of the columns that once graced this hall, six were usurped in antiquity and completely cut away. Most of the decorations funeral process. As we enter this hall turning left, we find a portrait of a guest at Ramose funeral banquet, including his mother, father, brother and sister-in-law. Note that most of these reliefs are unpainted with the exception of the eyes. Many scholars feel this particular scene represents one of the best pieces of ancient art to be found in the world. Every curl of a wig, bead of a necklace and soft fold of a garment is rendered in skilled detail.

Turning the corner, on the next wall is the funeral procession. The first scene is the only painted scene in the entire tomb (not relief), and shows servants carrying the burial riches of the deceased. In the next scene on this wall, a group of women with arms stretched to the heavens morn the loss of Ramose. This scene is considered a masterpiece of 18th dynasty art, portraying a real feeling of grief. But note that as we continue, their is less detail in the unfinished reliefs, and even some scenes that were only to the stage of being sketched.

On the left rear wall of the hypostyle hall is a scene of Ramose before Akhenaton and the goddess Ma’at, making offerings of flowers, while on the right rear wall the first scene is of Ramose being awarded the “gold of honor” by Akhenaton and his wife, Nefertiti. The second scene on this wall is of Ramose receiving a foreign delegation and also receiving flowers from the Temple.

There are no decorations on the next (west) wall. On the right front wall of this hall, we first encounter a scene depicting priests before the deceased and his family, along with a ritual list of magical offerings. Next comes a scene with three maidens with sistra before Ramose and his wife, purifying the deceased’s statue. The last scene is one of Ramose, his wife and bearers of offerings burning incense.

This hyperstyle hall leads to a second hall with eight columns, which in turn leads to the chapel at the rear of the tomb. However, this rear section of the tomb is currently closed.